Lymphoid tissue forms the basis of the immune system of the human body and is organized into diffuse and dense lymphoid tissue. The diffuse lymphoid tissue occurs as lymphoid cells infiltrate intro organ structures forming lymphatic aggregates , particularly evident in the subepithelial connective tissue of the digestive, respiratory, and urogenital tracts. The dense lymphoid tissue is a localized collection of lymphocytes organized into a compact, rounded structure called a lymphatic nodule or lymphatic follicle, which differs from a diffuse arrangement of lymphoid tissue. These nodules are found in connective tissue, particularly near mucosal linings in areas like the digestive and respiratory tracts and can form larger structures like tonsils or Peyer’s patches. They play a role in immune defense by producing lymphocytes and are often found where microorganisms are likely to enter the body.

Diffuse Lymphoid Tissue

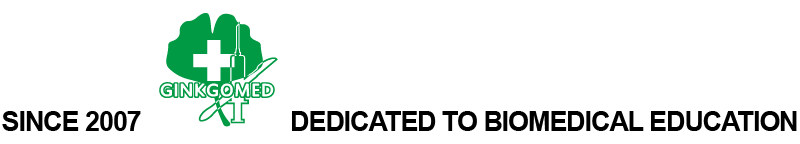

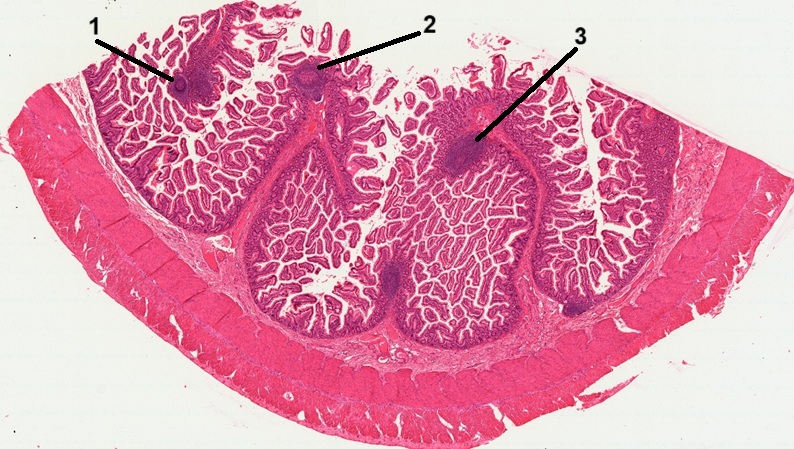

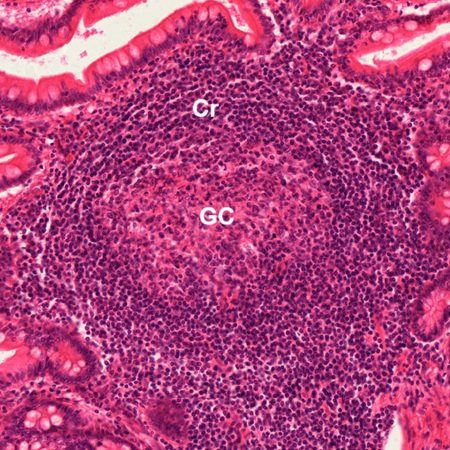

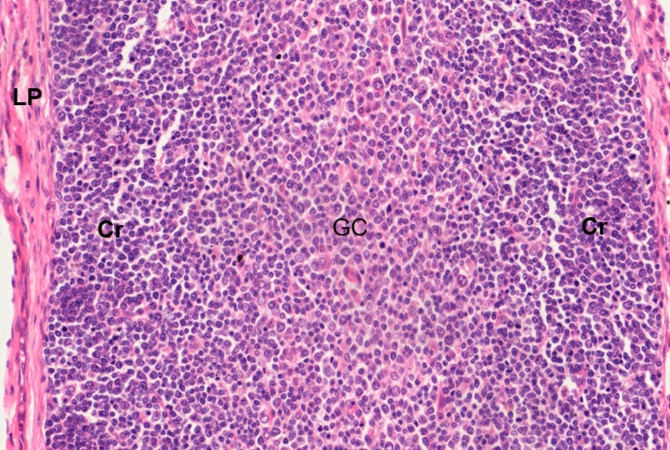

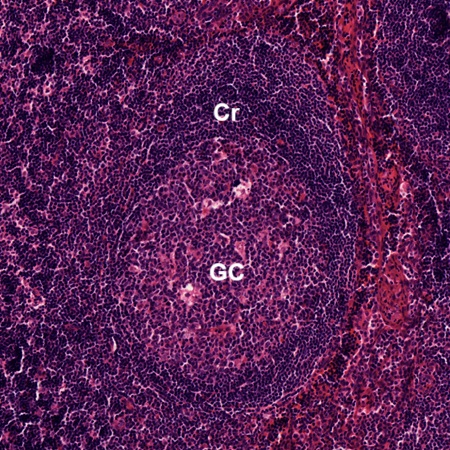

As stated above, lymphatic aggregates can be seen in the digestive tract. In a section of ileum stained by HE, six lymphatic aggregates are located (Fig. 9-1). Three of them form lymphatic nodules (1, 2, 3). As seen the Fig. 9-2, each of the lymphatic nodules has a germinal center (GC) and a darker, peripherally located corona (Cr). Other aggregates have lymphoid cells scattered in a haphazard manner (Fig. 9-3). Both types of lymphatic aggregates are limited in the lamina propria which is a thin layer of connective tissue under the intestinal epithelium.

The lymphoid tissue in the connective tissue under the mucosa membrane of gastrointestinal, respiratory and urogenital tracts, no matter if it is diffuse and nodular, has been considered to be a lymphoid organ and is collectively known as mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT).

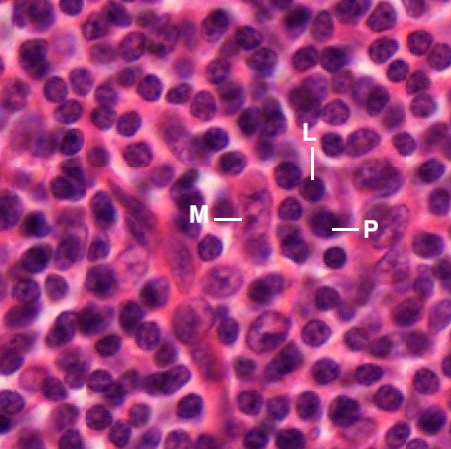

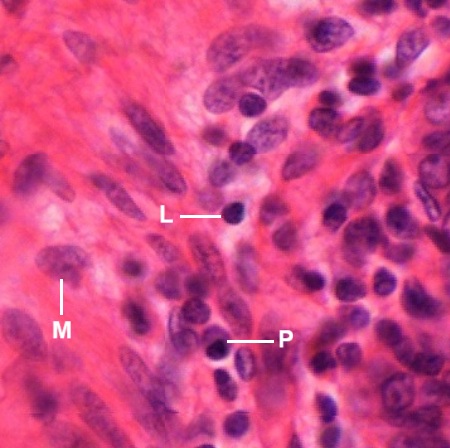

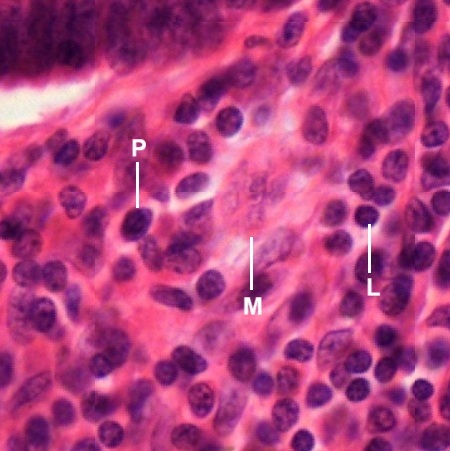

The lymphoid cells found in lymphoid tissue include lymphocytes (L), plasma cells (P), macrophages (M), reticular cells, dendritic cells. Although they are not easy to identify under the light microscope, some of them are still recognized in the following micrographs.

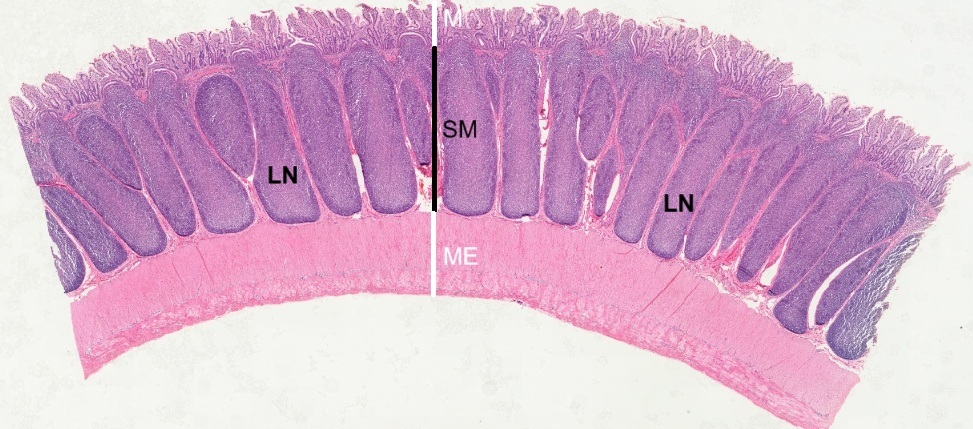

Peyer’s Patches

Peyer’s patches are aggregated lymphatic nodules, named after the 17th century Swiss anatomist Johann Conrad Peyer. They are an important part of gut associated lymphoid tissue (GLAT) mainly found in the distal portion of ileum (Fig. 9-7), and possible in duodenum and colon. They reside within the lamina propria (LP) under the mucosa (M), extend deep into the submucosa (SM) but above the muscularis externa (ME) of the intestinal wall. Each lymphatic nodule (LN) consists of a typical germinal center (GC) and a darker, peripherally located corona (Cr) regardless of its elongated shape and large size (Fig. 9-8).

Tonsils

Tonsils are aggregates of more or less encapsulated lymphoid tissue located at the entrances to the oral pharynx and to the nasal pharynx. Anatomically participating in the formation of the tonsillar ring are the palatine tonsil, pharyngeal tonsil, and lingual tonsil. Their histology structures are discussed here.

Palatine Tonsil

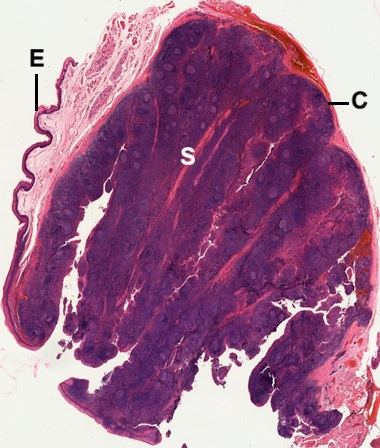

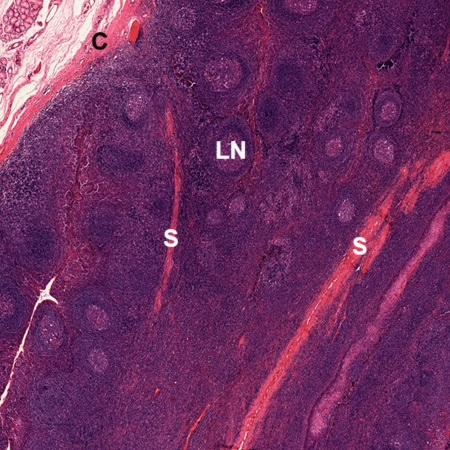

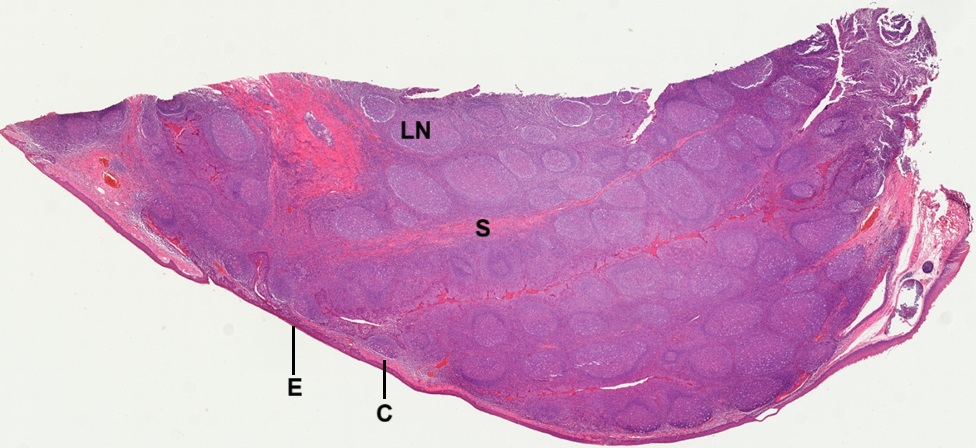

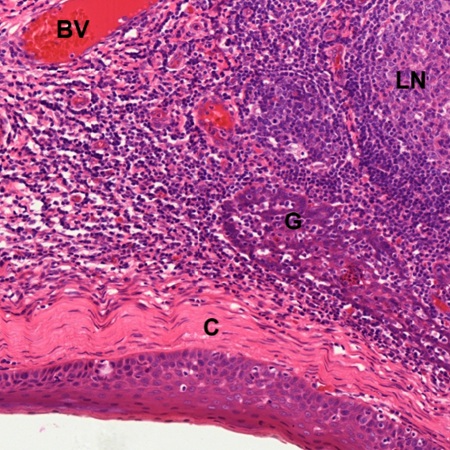

A section of palatine tonsil stained by HE (Fig. 9-9) reveals that a tonsil is embedded in the connective tissue covered by stratified squamous nonkeratinized epithelium (E). It consists of lymphoid tissue surrounded by capsule (C) composed of dense irregular collagenous connective tissue. Septa (S), derived from the capsule (C), are seen to extend into the tonsil (Fig. 9-10). Many lymphatic nodules (LN) are found inside the tonsil. Some lymphatic nodules display a germinal center with dark-stained corona (Cr) within the lymphoid tissue (Fig. 9-11).

Pharyngeal Tonsil

In a section of pharyngeal tonsil stained by HE (Fig. 9-12), as seen in the palatine tonsil above, many lymphatic nodules (LN) are packed as a mass of lymphoid tissue covered by capsule (C), which is composed of dense irregular connective tissue underneath the epithelium (E). Septa (S) are found within the lymphoid tissue. They are derived form the invagination of subepithelial dense irregular connective tissue (CT) which is not necessarily to form tonsillar capsule at this spot (Fig. 9-13). Lymphatic vessel (LV) is found. The covering epithelium is in a transition from stratified squamous epithelium (SSE) to columnar epithelium (CE). Sinuses (Sn) between the dense irregular connective tissue and lymphoid tissue are seen to contain lymphocytes. Components of seromucous gland (G) are also seen. In certain spot (Fig. 9-14), a solid capsule is formed between surface epithelium and lymphoid tissue. There are glandular components found at the edge of lymphoid tissue containing lymphatic nodule (LN) and blood vessels (BV) nearby.

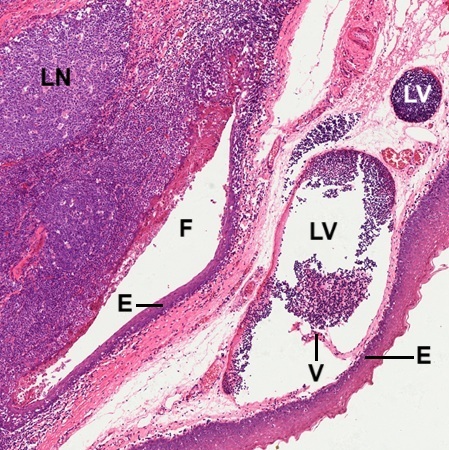

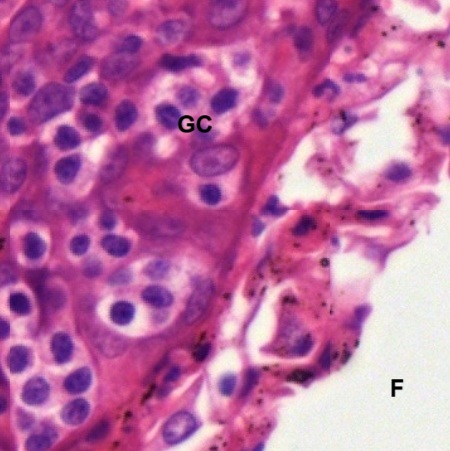

Crypt-like fold (F) with invagination of covering epithelium (E) and subepithelial connective tissue is seen (Fig. 9-15). There are lymphatic vessels (LV) filled with lymphocytes found in the subepithelial connective tissue. One of them has a lymphatic valve (V) extending from vascular wall. Along with the fold (F), glandular cells (GC) of seromucous gland attached can be seen (Fig. 9-16). Organization of lymphatic nodules of the pharyngeal tonsil are the same as those of the palatine tonsil (Fig. 9-17). Each has a germinal center (GC) surrounded by a darker corona (Cr).

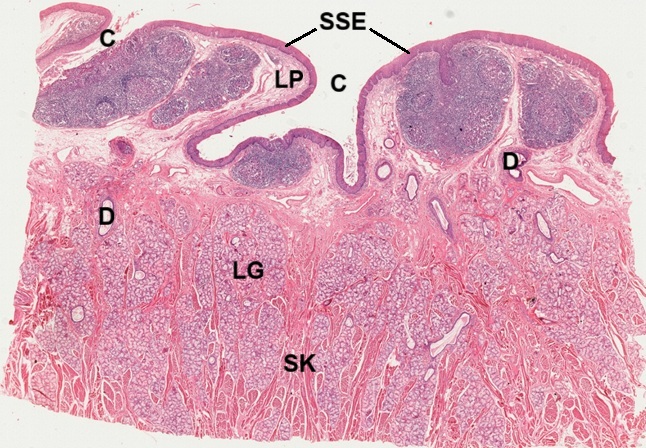

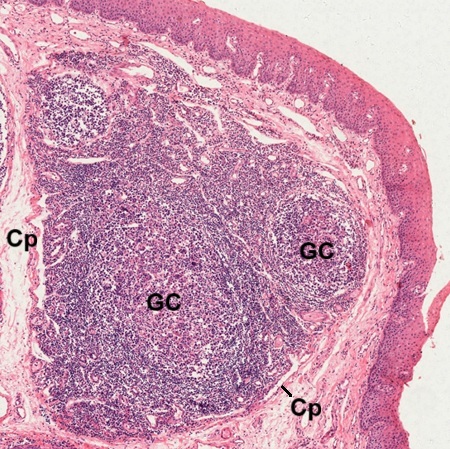

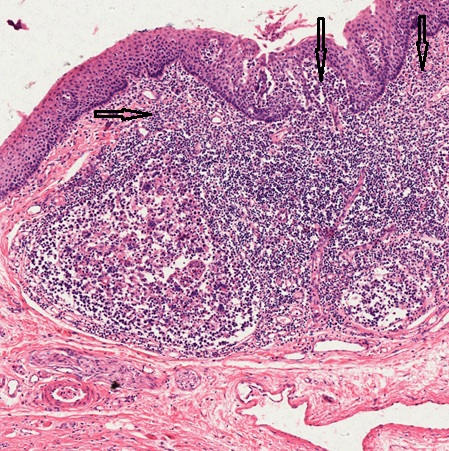

Lingual Tonsils

Lingual tonsils are collections of lymphoid tissue located in the lamina propria of the root of tongue that act as a first line of immune defense against pathogens entering the body through the mouth. In a section of stained the root of tongue by HE (Fig. 9-18), It is shown that crypts (C) invaginated from the surface covered by stratified squamous nonkeratinized epithelium (SSE). In the lamina propria (LP) underneath the epithelial surface there are lymphoid tissue, while in the deeper portion of the section a lot of lingual glands (LG) are found within bundles of skeletal muscle fibers (SK). Glandular ducts (D) extending toward the epithelial surface. Lymphatic nodules with geminal centers (GC) can be seen as in other tonsils (Fig. 9-19). A thin and not well defined capsule (C) is found to be formed by collagenous fibers in the lamina propria. Lymphocytes are not limited within the lymphatic nodules (Fig. 9-20). They are found to infiltrate into the lamina propria and even the epithelium as indicated by arrows.

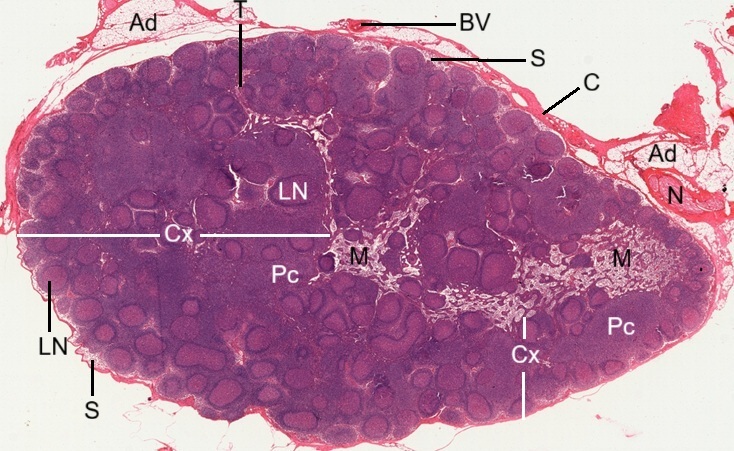

Lymph Nodes

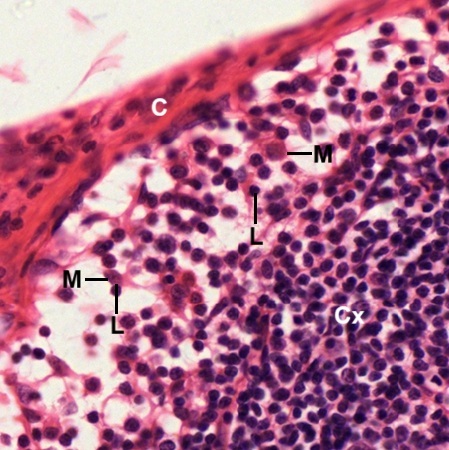

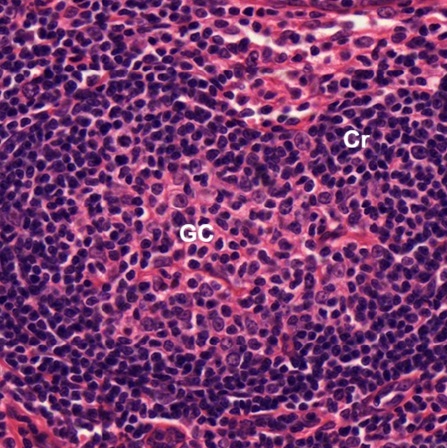

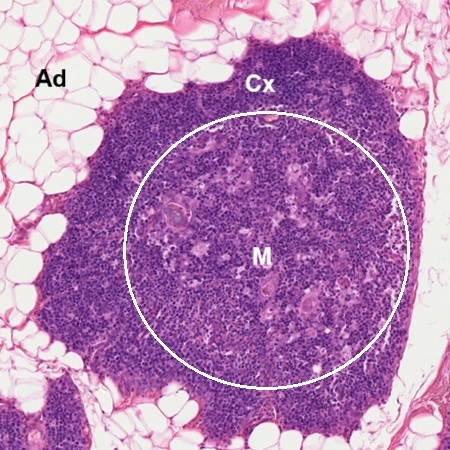

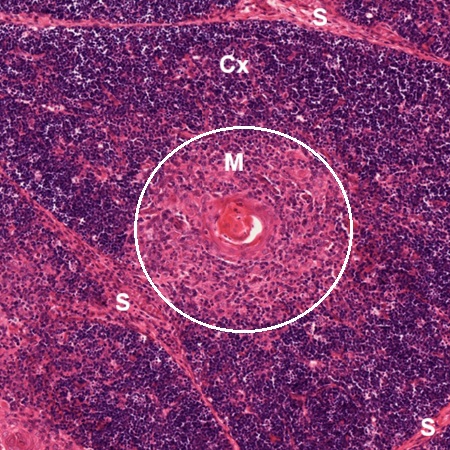

A section of lymph node stained by HE (Fig. 9-21) reveals that it is covered with a capsule (C) composed of dense irregular collagenous connective tissue. Adipose tissue (Ad), blood vessel (BV), and nerve bundle (N) are seen to attach with the capsule, that sends trabeculae (T) into the substance of the node. Underneath the capsule (C) is subcapsular sinuses (S). The lymph node is composed of outer cortex (Cx) and inner medulla (M). The superficial cortex contains lymphatic nodules (LN), also known as lymphatic follicles. The deeper paracortex (Pc), also known as the T-cell zone, is the layer situated between the outer B-cell-rich cortex (Cx) and the medulla (M). In the subcapsular sinuses between capsule (C) and lymphatic cortex (Cx), lymphocytes (L) and microphages can be identified (Fig. 9-22). As seen in the above lymphoid tissue, each lymphatic nodule (Fig. 9-23) possesses a dark staining corona (Cr), composed of mainly small lymphocytes, and a germinal center (GC). The germinal center displays numerous cells with lightly stained nuclei, including dendritic reticular cells, plasma blasts, and lymphoblasts.

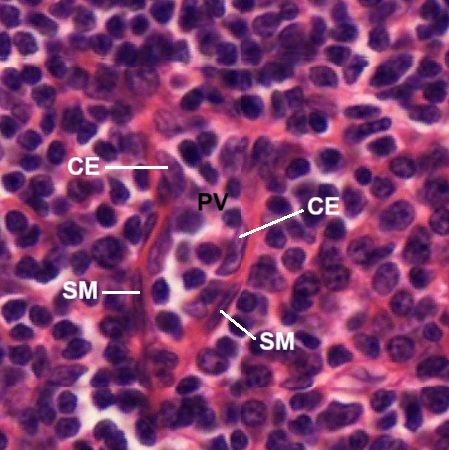

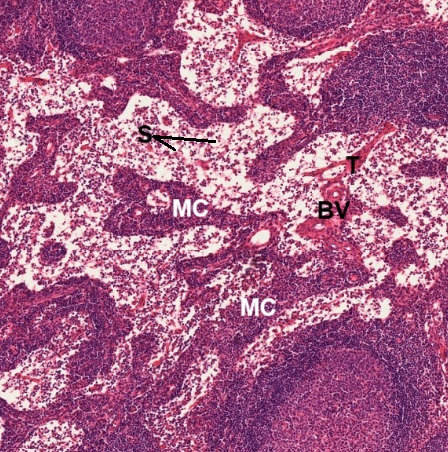

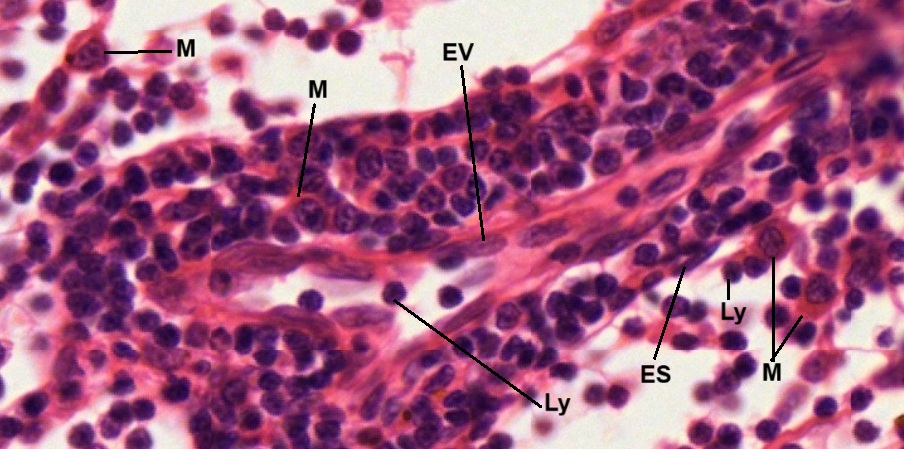

The paracortex contains specialized blood vessels called postcapillary venules (PV) within lymphoid cells (Fig. 9- 24). These venules can be distinguished by their cuboidal endothelial cells (CE) and smooth muscle fibers (SM). Circulating lymphocytes enter the lymph node through these venules. The medulla is the lighter staining zone surrounded by the cortex and paracortex (Fig. 9-25). It is composed of medullary cords (MC), sinusoids (S, blank space), and trabeculae (T) of connective tissue conducting blood vessels (BV). Lymphocytes (Ly) and macrophages (M) can be identified in the medulla (Fig. 9-26). One medullary cord is seen to carry a lymphatic vessel containing lymphocytes in the lumen, which has a thin wall made of endothelium (EV). A lymphocyte– containing sinusoid also has a thin wall made of endothelium (ES).

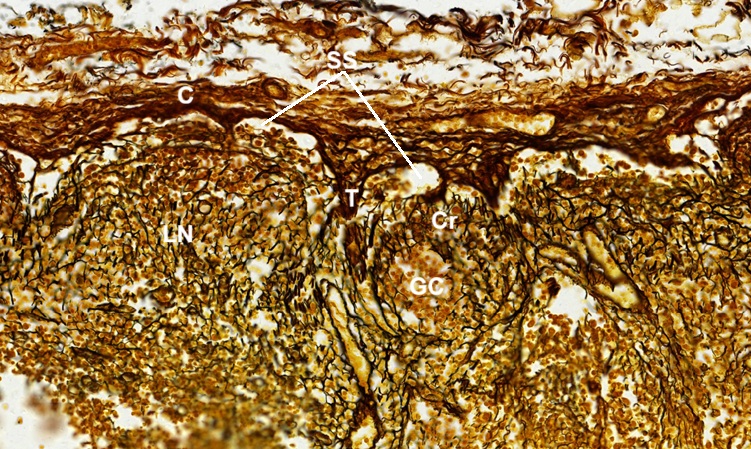

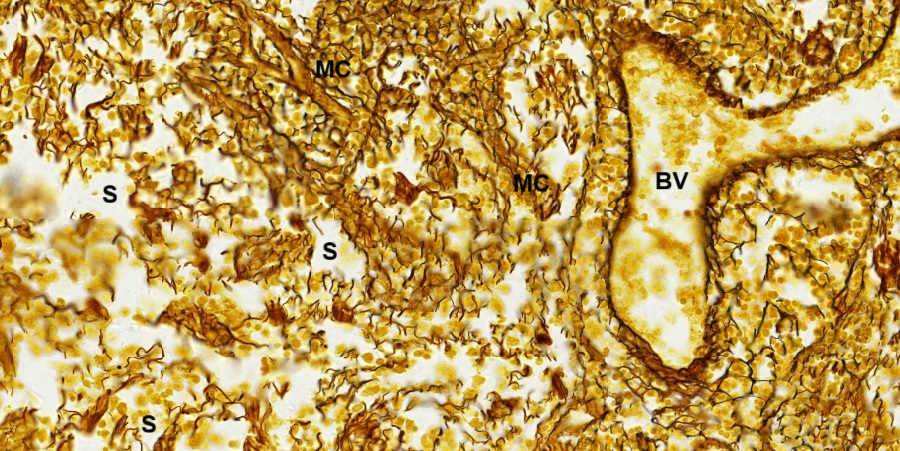

The main structural support for the lymph node is derived from the collagenous capsule and trabeculae, which extend into the node. To visualize this supporting framework of a lymph node, a section stained by SI is observed. It is shown that reticular fibers (stained blackish brown) from the capsule (C) and trabeculae (T) form a fine meshwork in the lymphatic cortex (Fig. 9-27). The reticular network is particularly dense in corona (Cr) of lymphatic nodule (LN), but relatively sparse in germinal center (GC). Nuclei of lymphoid cells are found to be stained light brown. Subcapsular sinuses (SS) can be recognized by their reticular outline. In the lymphatic medulla (Fig. 9-28), fewer reticular fibers are seen but medullary cords (MC), blood vessels (BV), and even sinusoids (S) still can be outlined.

Spleen

Human spleen is an encapsulated lymphatic organ underneath the left part of the diaphragm in the abdominal cavity. Its smooth convex surface faces the diaphragm. The concave surface is in contact with the posterior wall of the stomach. On the concave surface there is a long fissure, the hilum, which is the point of attachment for the gastrosplenic ligament and the point of insertion for the splenic artery and splenic vein. There are other openings present for lymphatic vessels and nerves. In addition to the splenic artery, largest branch of the celiac artery, collateral blood supply is provided by the adjacent short gastric arteries. The spleen possesses only efferent lymphatic vessels. It is related to its functions of filtering blood, removing old and damaged red blood cells, and helping fight infection by producing white blood cells lie lymphocytes and macrophages.

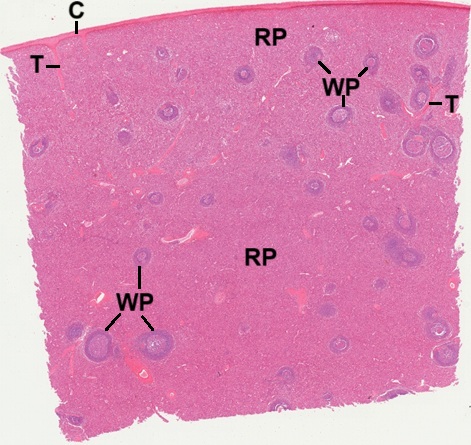

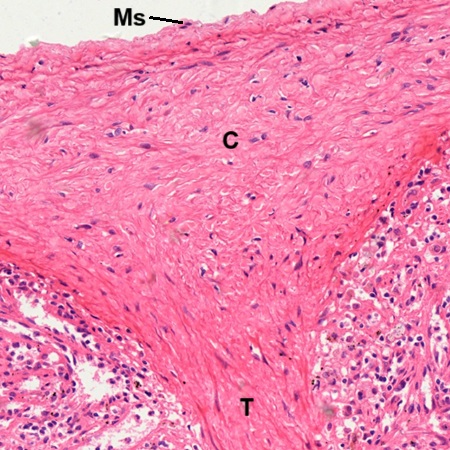

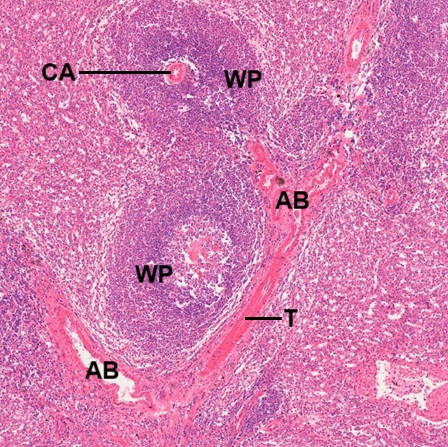

A section of spleen stained by HE is observed (Fig. 9-29). Its surface is enveloped by a layer of capsule (C), which extends to form trabeculae (T) into the parenchyma. Microscopically, the spleen section appears to consist of lymphatic nodules, called the white pulp (WP), embedded in a red matrix called the red pulp (RP). The capsule (C) is a thin but dense fibroelastic connective tissue covered by mesothelium (Ms) which is derived from the peritoneum (Fig. 9-30). A trabecula (T) is seen to extend from the capsule. Branches (AB) from the splenic artery enter the parenchyma through the passage of the trabeculae (T), which also contain venous drainages back to the splenic vein (Fig. 9-31). Eventually these arterial branches become central arteries (CA) surrounded by lymphoid tissue called white pulp (WP).

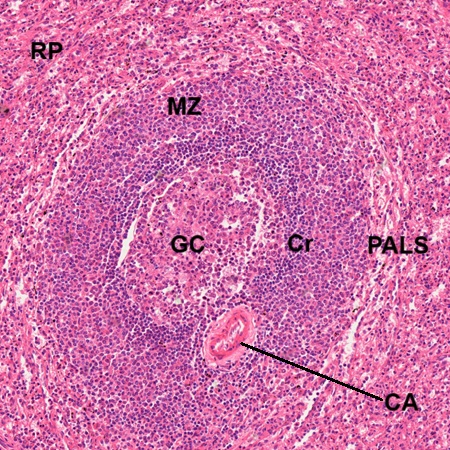

White pulp, embedded within the red pulp (RP), is composed of periarterial lymphatic sheath (PALS) and lymphatic nodule with a light stained geminal center (GC) and dark stained corona (Cr),as seen in other lymphoid tissue (Fig. 9-32). The lymphatic nodule frequently occurs at branching of the central artery (CA). The marginal zone (MZ) around the lymphatic nodule is the region where lymphocytes leave the small capillaries and first enter the connective tissue space of the spleen. The germinal center may contain immature lymphocyte, plasmablast, follicular dendritic cell and macrophage (Fig. 9-33). Without special staining, such as immunocytochemical stains, most of them cannot be identified positively.

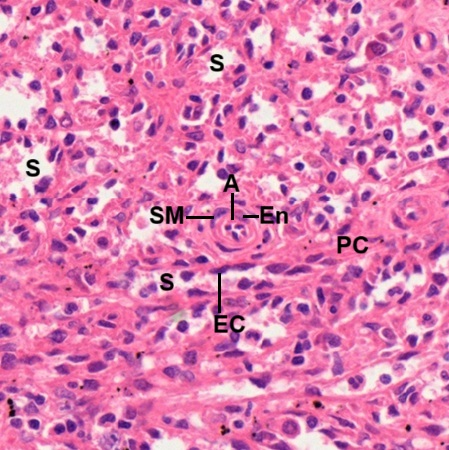

The red pulp of the spleen is composed of venous sinusoids (S) and pulp cords (PC) or parenchyma in certain textbook (Fig. 9-34). The sinusoids (S) are lined by a discontinuous type of epithelium whose endothelial cells (EC) bulge into the lumen. The vascular supply of the red pulp is derived from penicillar arteries branching into arterioles (A), whose endothelial cell (En) and smooth muscle fiber (SM) are evident in the center of this field. In the red pulp (RP),blood flow of venous sinusoids eventually will drain into the venules (V) contained in the trabecula (T). A branched artery (BA) in the other trabecula is seen nearby (Fig. 9-35).

Thymus

The thymus is a lymphoid organ located in the upper anterior mediastinum and lower part of the neck. It is most active during childhood. Then it undergoes slow involution, which is the natural, age-related shrinkage of the thymus, where its functional tissue is progressively replaced by adipose tissue.

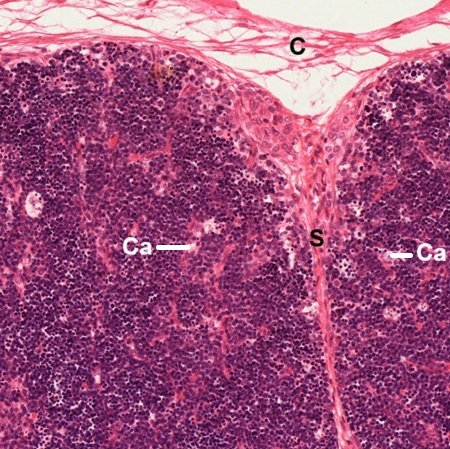

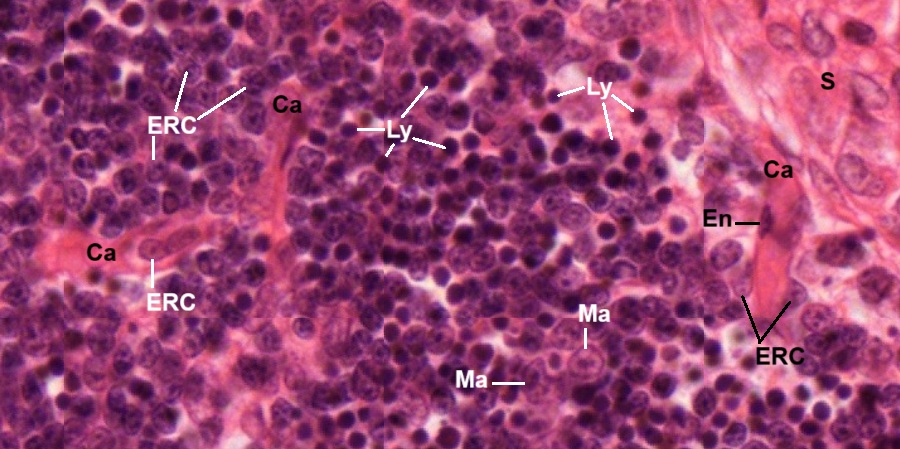

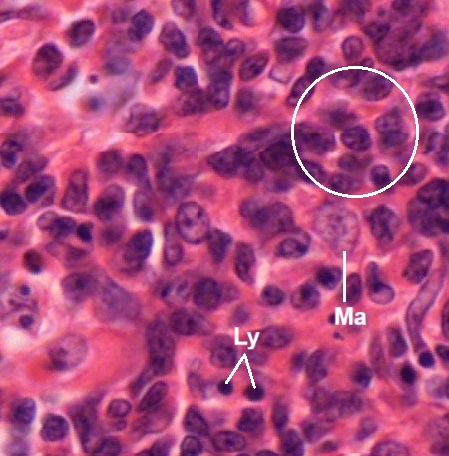

A section of infant thymus stained by HE (Fig. 9-36) reveals that the infant thymus is a lobulated organ invested by a loose collagenous capsule (C) from which interlobular septa (S) containing blood vessel (BV) invaginate into the organ and divide the thymus into lobules (Lb). Each lobule of the thymic tissue is divided into outer basophilic cortex (Cx) and inner eosinophilic medulla (M). The thymic cortex has no lymphatic nodules or plasma cells. Fig. 9-37 shows two adjacent thymic lobules separated by septum (S) which is extended from the capsule (C) . Many capillaries (Ca) are found inside the cortex. At high magnification (Fig. 9-38), it is revealed that the cortex is composed of light stained epithelial reticular cells (ERC), macrophages (Ma), and dense stained lymphocytes (Ly), or called thymocytes. Three capillaries (Ca) are shown . One of them appears to be coming from the septum (S). An endothelial cell (En) of the capillary wall is seen. Neither reticular fibers nor sinusoids are found in the thymic cortex.

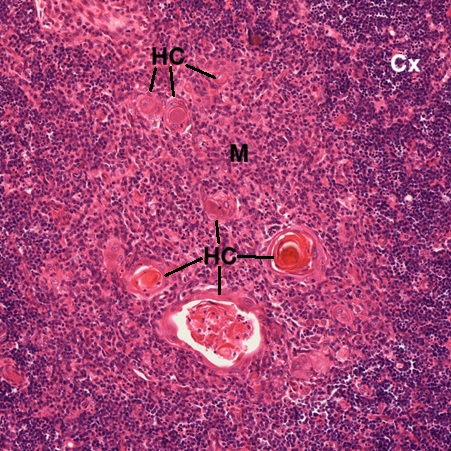

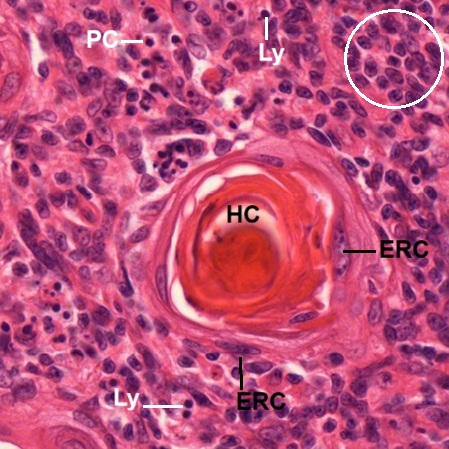

The thymic medulla (M) is different from the thymic cortex (Cx), not only due to cellular components but most importantly the presence of Hassal’s corpuscles (HC) or called thymic corpuscles. The micrograph shows at least seven corpuscles have been formed or in the process of formation (Fig. 9-39). At high magnification (Fig. 9-40), one Hassal’s corpuscles (HC) appears to have a central mass surrounded by concentric layers of epithelial reticular cells (ERC). The function of the corpuscle is still unclear. Cells around the corpuscle include the predominant thymic epithelial cells (circled ones), the lymphocytes (Ly), few plasma cells (PC), and other morphologically unidentified cells. In the other field (Fig. 9-41), macrophage (Ma) can be found within abundant thymic epithelial cells (circled ones) and fewer lymphocytes (Ly).

Thymic Involution

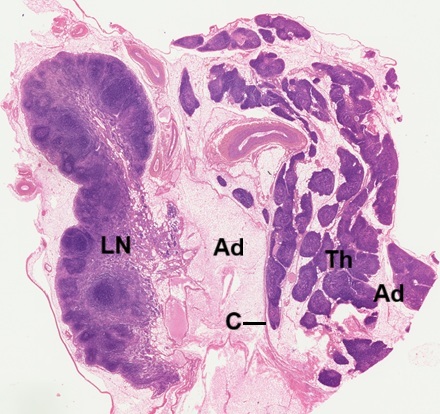

Thymic involution is a genetically programmed ageing process resulting in changes of thymic architecture and a decrease in tissue mass. In a section of adult thymus (Fig. 9-42), the thymus is found to be as small as the adjacent lymph node (LN), which is cut together with the thymus (Th). Adipose tissue not only occupies the space outside the thymic capsule (C) but also infiltrates into space between thymic lobules. Total size of thymic tissue is apparently decreased. Taking one adult thymic lobule (Fig. 9-43) to compare with one young thymic lobule (Fig. 9-44), it is found that the adult one is entirely surrounded by adipose tissue (Ad) while the young one is separated from adjacent lobules by septa (S). In adult thymus (Fig. 9-43), the medulla (M, within the circle) has almost the same basophilic staining as the cortex (Cx). In young thymus (Fig. 9-44), the medulla (M, within the circle) appears to be stained eosinophilic, but the cortex (Cx) is stained basophilic. The Hassal’s corpuscle (HC) is still present in the adult medulla (Fig. 9-45). Compared with the young medulla (Fig. 9-40), apparently more lymphocytes are seen in the adult one.

NOTE:

- Only those organelles visible under the light microscope are discussed here. It is suggested that to study all organelles visible under the electron microscope through your histology textbook and atlas.

- All photos used for discussion are taken from DSMH digital slides and other source as follows:

H070010 Lymph Node, sec., human, HE. (Figs. 9-21, 9-22, 9-23, 9-24, 9-25, 9-26)

H070012 Lymph Node, sec., human, SI. (Figs. 9-27, 9-28)

H070020 Palatine Tonsil, sec., human, HE. (Figs. 9-9, 9-10, 9-11)

H070030 Pharyngeal Tonsil, sec., human, HE. (Figs. 9-12, 9-13, 9-14, 9-15, 9-17)

H070040 Lingual Tonsil, sec., human, HE. (Figs. 9-18, 9-19, 9-20)

H070050 Spleen, sec., human, HE. (Figs. 9-29, 9-30, 9-31, 9-32, 9-33, 9-34, 9-35)

H070060 Adult Thymus, sec., human, HE. (Figs. 9-452, 9-43, 9-45)

H070070 Infant Thymus, sec., human, HE. (Figs. 9-36, 9-37, 9-38, 9-39, 9-40, 9-41, 9-44)

H070100 Peyer’s patch, cs. of ileum, human, HE, showing lymphatic aggregates. (Figs. 9-4, 9-5, 9-6)

H090220 Ileum, cs., human, HE. (Figs. 9-1, 9-2, 9-3)

H090230 Small Intestine Composite, cs. of three intestine portions, human, HE. (Figs. 9-7, 9-8) - Staining abbreviations and results:

HE = hematoxylin and eosin, is used to stain cell nuclei blue and cytoplasm pink or red. Hematoxylin may also stain ribosomes and rough endoplasmic reticulum blue.

SI = silver impregnation, used to demonstrate neurons and processes in black or brown.